Manufacturers Index - Massachusetts Caloric Engine Co.

Massachusetts Caloric Engine Co.

South Groton, MA; Boston, MA, U.S.A.

Manufacturer Class:

Steam and Gas Engines

Last Modified: Oct 27 2019 4:52PM by Jeff_Joslin

If you have information to add to this entry, please

contact the Site Historian.

|

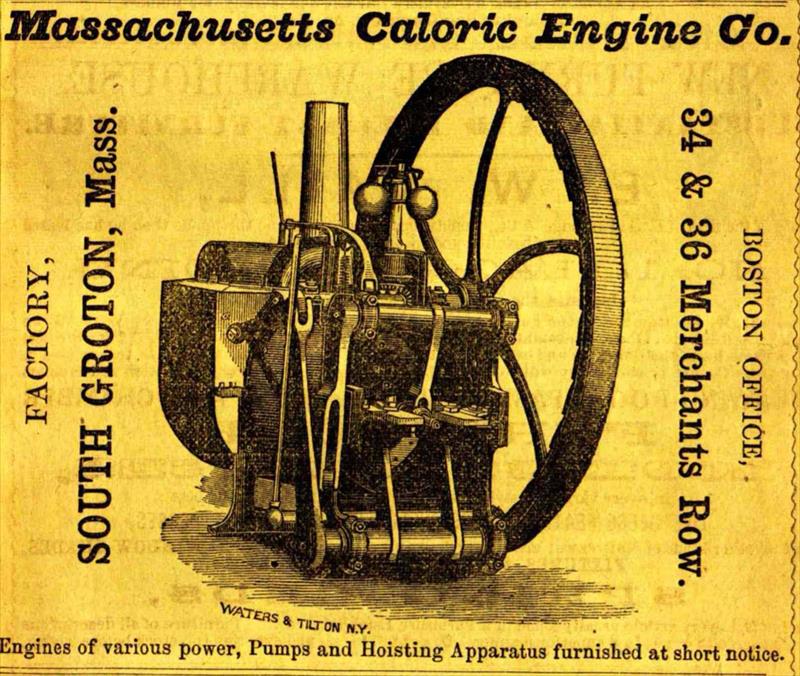

During the late 1850s and early 1860s the Massachusetts Caloric Engine Co. was manufacturing inventor John Ericsson's atmospheric engines in South Groton, Massachusetts, with sales office in Boston. These kinds of engines were much less efficient that steam engines, but were considered to be safer and required less maintenance, and were well suited for applications where not more than about 4 HP is required. The company reportedly manufacturing over 4,000 engines in its lifetime but they seem to have disappeared during the U.S. Civil War.

|

| From 1860 Worcester Directory |

John Ericsson

John Ericsson was a Swedish-born American and a prolific inventor. While living in England in 1829 he rushed to build a steam locomotive to compete against the famous George Stephenson locomotive in a trial; Ericsson's resulting design was in many respects superior to Stephenson's but during the trial Ericsson's engine broke down and Stephenson's went on to win. Ericsson abandoned his locomotive effort and returned attention to a previous obsession, devising an engine to convert combustion heat to mechanical motion without steam, which Ericsson viewed as unacceptably dangerous in many applications. He developed the external-combustion "atmospheric engine" that used the heating and cooling of air to drive over-sized pistons.

He demonstrated his new engine in London, patented it and then turned his attention to boat propulsion. The idea of the propellor was not new but Ericsson is credited as the first to make it practical. A demonstration to the British Admiralty failed, apparently due to the Admiralty's disbelief that a relatively small propeller could be more efficient than a paddle-wheel, even though Ericsson's small propellor-powered boat towed a barge considerably faster than a paddle-wheel boat could.

Ericsson moved back to America and resumed work on his atmospheric engine. In 1853 he built four enormous atmospheric engines to power a 260' 200 ton ship, the U.S.S. Ericsson. Each engine had a cylinder of 14 feet diameter and the pistons had a stroke of 6 feet. Ericsson designed them to produce a total of 2,400 HP, but they only produced half that—it would seem that Ericsson did not fully understand the limitations of scaling up his engine design. He did not use his controversial blade propellors, electing for side-mounted paddle wheels 32 feet in diameter. Presumably because of the engines' lack of power, the ship achieved a disappointing 8 knots. Fuel consumption was also disappointing, though still superior to that of a conventional steam engine. The following year the U.S.S. Ericsson sank just outside New York Harbor.

A few years later the Massachusetts Caloric Engine Company was established. We do not know the extent of Ericsson's involvement.

With the onset of the Civil War, Union officials asked Ericsson to design and construct an iron-clad vessel. The gave him $275,000 and 100 days to complete the design and build. The resulting vessel, launched in 1862, was the Monitor. Displacing nearly 1,000 tons and powered by a pair of 160HP steam engines, it had a top speed of nine knots. It March of 1862 it faced off against the Confederate's Virginia (which had been rechristened by the Confederates after they had salvaged the northern-built Merrimack from the Virginia shipyards) . Both crews were inexperienced and the aiming of their guns was inaccurate. The Monitor was faster and more maneuverable but was hampered by guns that took nearly eight minutes to reload. The Monitor's pilot house was hit, injuring the captain. They retreated to shallow waters; the Virginia/Merrimack, damaged and low on ammunition, returned to its port. The battle marked the end of the era of wooden warships. The Virginia/Merrimack was destroyed by its crew when during the May 1862 evacuation of Norfolk. The Monitor sank during a storm in December of the same year.

Information Sources

- February 1860 Southern Cultivator

Ericsson's Caloric Engine:—A. C. H.—We find the following remarks in one of our New York exchange papers: "Owing to the danger of generating steam without constant attention and care, the Ericsson Engine is rapidly being introduced for pumping, hoisting, and other purposes, where but little power is required. The machine is simple, perfectly safe, and with due attention to the regulation of heat, is not liable to disarrangement. There are inherent difficulties in the use of atmospheric air which will probably prevent its ever taking the place of steam for marine and other large engines, but from its safety, economy, and reliability, it is taking the place of horse and manual labor wherever it is adapted to the work performed, the consumption of a few pounds of coal per day being found much cheaper than its equivalent in muscle of man or beast." The Editor of the Maine Farmer also speaks very highly of one of these engines that he has in constant use for the purpose of running his press. He says: "To a certain extent—say eight or ten horse power —it is one of the safest, most easily managed and most economical engines that can be used;" and adds: "Ours is an 18-inch cylinder—rated at two horse power. Wc have geared it so as to drive our large Adams Power Press at a speed of from 900 to 1100 impressions per hour. It does this at a cost for fuel of only 2.5 cents per day of 12 hours. Anybody who can build a fire, can put and keep it in operation; and its motion is steady and uniform. Thus far its work has been perfectly satisfactory. The engine was manufactured by the Massachusetts Caloric Engine Company, South Groton, Mass., and cost $550 delivered in Boston." We should think one of these engines well adapted to the driving of a Cotton Gin, and useful for many other purposes on the Plantation.

- The Smithsonian National Museum of American History has a listing for an 1859 catalog from Massachusetts Caloric Engine Co., for "Ericsson's caloric engine".

- 1927 Dearborn Independent (Volume 28, Issue 7, page 5).

...so small that he could not reach the eyepiece of his leveling instrument, and had to be followed everywhere by an attendant carrying a stool. Later he entered the Swedish army. At that time all the field surveying was done by army officers and so he became a government surveyor. Full of energy, he spent all his spare time experimenting and inventing, and his particular interest at this time was to find a means of producing mechanical power by the use of flame. Eventually he contrived a flame engine, by means of which sufficient power could be produced to pump water to a considerable height, and he received a leave of absence to go to England to introduce his invention there. But the flame engine did not achieve success: funds ran low, and Ericsson had to look around for employment. Although at this time he was only twenty-three years old he was so obviously master of his subject that he inspired the greatest confidence in those with whom he came in contact, and it was not long before the manufacturing house of John Braithwaite took him into the firm as junior partner. He afterward acknowledged that he owed much of his later success to the experience which he gained at this time through the friendship and co-operation of Braithwaite.

The tale of Ericsson's life is that one one long series of inventions. One of his achievements was the invention of a pumping engine for draining mines, in which for the first time compressed air was used to produce power. He also invented several devices for improving marine engines, of which the most important was the surface steam condenser. Another was a steam fire engine, which could throw water to the tops of the highest buildings of that day. But so many objections were raised to this innovation that it was not until 1860 that a machine of similar design was finally brought into use to fight the London fires, and to replace the squirts and hand pumps which had been used up to that time.

In 1829 Eriscsson turned his inventive genius into a new field. Up in the colliery district of the north of England, Stephenson had been working for some time on the steam locomotive. Horse-drawn trams for hauling coal were already in use, but the idea that sufficient power to draw the heavy loads could be produced by steam was ridiculed as absolutely impossible. However, Stephenson finally persuaded the officials of the...

...Ericsson heard of the offer seven weeks before the date set for the contest, and at once set to work to build an engine. Although he had never made a locomotive, his quick mind immediately grasped the problems of its construction, and when the day for the trial came, Ericsson's Novelty, with its system of artificial draught, was a serious competitor to Stephenson's famous Rocket. But although the Novelty reached a speed of thirty miles an hour, and easily shot past the Rocket, it developed several minor defects which would undoubtedly have been overcome if there had been time for preliminary tests, and was unable to finish the required distance of seventy miles. Although it was generally admitted that the principles of the construction of the Novelty were the more scientific, the prize went to Stephenson

Disappointed in the result, Ericsson lost interest in locomotives, and turned back to the flame engine, and was soon astonishing London with a five-horsepower caloric engine. He next began to experiment with screw propellers, and was so pleased with the results that he built a boat forty feet long which could tow a schooner at the rate of seven miles an hour. This he demonstrated before the British admiralty, but as is...

- From an 1993 issue of Tech Directions.

Steam engines started to be used in locomotives and ships in the early 1800s. John Ericsson, a Swedish-born American, was concerned about steam boiler explosions. He designed a unique external combustion engine that used used air instead of steam to move a piston. Four of his engines successfully powered a 260' ship, the U.S.S. Ericsson, from New York to Washington, DC, in 1853. Ericsson was born in 1803, the youngest of three children. His father was a mining engineer who provided secure financial support. His mother had an excellent education and made sure her children received superior instruction. As he grew up, Ericsson demonstrated an aptitude for repairing mechanical equipment. He worked on government canals as a 13-year-old cadet and learned mathematics, drafting, and English. He showed particular skill on the drawing board, and became an army topographic officer in in 1820. It was during this period that he developed an interest in the air engine. Ericsson moved to London in 1826 and received 14 British patents for inventions such as steam engine boilers, centrifugal blowers for forced ventilation, and a steam locomotive. In 1836, he developed the first successful blade-type propeller, which was used on a canal boat that ran between Manchester and London. It was the first use of a propeller in commercial service. The British navy was not interested in propellers, so Ericsson returned to America in 1839. Because of his understanding of mechanical principles, he never had trouble finding employment. He did not invent the propeller, but he refined it made using it practical—perhaps his greatest accomplishment.

Although he kept busy, Ericsson always found time for his pet project, air (caloric) engines. Small and quite inefficient, they were most suitable for low power applications and were primarily used to pump water for homes. Even so, his Massachusetts Caloric Engine Company sold more than 4,000 engines. Like electrical motors, caloric engines were useful in small sizes but could not be readily scaled up for larger power applications. Ericsson was unprepared for that problem when he built four huge caloric engines for the 1853 demonstration of the 200 ton U.S.S. Erricsson. Each of its engines had a cylinder diameter of 14' and a stroke of 6'. He expected them to produce a total of 2,400 hp, but they only reached half that power. Side-mounted paddle wheels 32' in diameter drove the ship through the water—at a slow eight knots. Fuel consumption was double the expected amount but still less than comparable steam engines. Before he could conduct any conclusive tests, the ship sank just outside New York Harbor in 1854. Ericsson regularly worked with the Navy, and Union officials curing the Civil War asked him to build an iron-clad vessel. He accepted the assignment and was given $275,000 and 100 days. The boat he designed displaced almost 1,000 tons of water, used two 160 hp steam engines, and had a top speed of nine knots. His 172' Monitor was launched in 1862, the same year it met the Confederate Merrimac off Norfolk, VA. Their renowned battle was the first between steam- powered ironclads. Although a brilliant and persistent inventor, Ericsson lost interest in a project once it was completed. He died in 1889 in New York City.

|